I could not agree more with this sentiment. Between the three different majors I have switched between over the course of my college career, I always find myself coming away from each semester not necessarily with an abundance of newfound knowledge, but a greater expansion of my mental abilities. In many ways, the human brain is similar to an automobile; different parts can be swapped out, new parts can be brought in, all with the same goal of making the car faster. Eventually however, all cars end up in the junk yard. The brain differs in that its potential for expansion and improvement is endless. While some people may have more enhanced skills in certain ways of thinking, everyone has the potential to improve.

I have always thought of

myself to have a poor memory. I used to have difficulty remembering information

for exams, phone numbers, names, etc. What this class has taught me is that any

memory can be improved with the proper type of training. The visuality and

spatial awareness that is so crucial to our mental programming, that all of the

authors we have read elaborate on, is truly enlightening. The first things I

memorized for this class were Foer's 15 items, and I was blown away by how

quickly it was accomplished by using the beautiful simplicity of the memory

theater. At first constructing imagery to place in theaters was difficult and

time consuming, but similar to any skill I found that it got exponentially

easier with practice. I found that even poetry can be easily mastered using

mnemonic techniques. Foer and many others claim that poetry is most easily

mastered by rote, but I strongly disagree. It does not take exceptional

intelligence to create imagery for verse, but simply the ability to be flexible

and creative. When constructing imagery around lines of poetry, the

biggest challenge I faced was that I got too hung up on trying to match

the perfect image with every line. This is simply not realistic. To efficiently

use a memory theater for this purpose, I discovered that I had to allow myself

to adapt quickly during the mental walk-throughs of my theaters. In

Kubla Kahn for example, I did not have time to stray from the route I was

visualizing to find something perfectly suitable for the line "So twice

five miles of fertile ground, with walls and towers were girdled round",

so I made something work. In my mind I was in my parents house in front of the

pool table at that point in the poem, so I imagined the top of the pool table

piled high with dark, rich, recently plowed soil. As for the walls and towers,

the cue stand next to the table was transformed into a classical Greek tower

with the cues serving as the pillars. I could go on and on explaining the inner

workings of my various palaces, but I'm afraid that it would consume dozens

of pages.

I have always thought of

myself to have a poor memory. I used to have difficulty remembering information

for exams, phone numbers, names, etc. What this class has taught me is that any

memory can be improved with the proper type of training. The visuality and

spatial awareness that is so crucial to our mental programming, that all of the

authors we have read elaborate on, is truly enlightening. The first things I

memorized for this class were Foer's 15 items, and I was blown away by how

quickly it was accomplished by using the beautiful simplicity of the memory

theater. At first constructing imagery to place in theaters was difficult and

time consuming, but similar to any skill I found that it got exponentially

easier with practice. I found that even poetry can be easily mastered using

mnemonic techniques. Foer and many others claim that poetry is most easily

mastered by rote, but I strongly disagree. It does not take exceptional

intelligence to create imagery for verse, but simply the ability to be flexible

and creative. When constructing imagery around lines of poetry, the

biggest challenge I faced was that I got too hung up on trying to match

the perfect image with every line. This is simply not realistic. To efficiently

use a memory theater for this purpose, I discovered that I had to allow myself

to adapt quickly during the mental walk-throughs of my theaters. In

Kubla Kahn for example, I did not have time to stray from the route I was

visualizing to find something perfectly suitable for the line "So twice

five miles of fertile ground, with walls and towers were girdled round",

so I made something work. In my mind I was in my parents house in front of the

pool table at that point in the poem, so I imagined the top of the pool table

piled high with dark, rich, recently plowed soil. As for the walls and towers,

the cue stand next to the table was transformed into a classical Greek tower

with the cues serving as the pillars. I could go on and on explaining the inner

workings of my various palaces, but I'm afraid that it would consume dozens

of pages. When I was

brainstorming concepts for my musey room, I had trouble coming up with an idea

that would effectively encompass what I have learned from this course. I

realized that it would be impossible to give anyone a visual glimpse into my

newfound memory systems, due to their grotesquely abstract complexities that

make them so uniquely memorable. The reason that they cannot be explained to

another person is that they are so incredibly visual. This is largely a result of the practicality of rehearsing

poetry aloud. Due to people thinking you're crazy, and limited alone time, I

had to be able to utilize silence during the construction of my memory

theaters. This is a difficulty I ran into while learning Kubla

Kahn. To accommodate for the restraints presented, I created

imagery for the entire poem without speaking a single word. Before I ever

practiced the poem in length for the first time, I had detailed images

constructed in my mind. I did almost all of my memory training this semester on

the third floor of the library, in the quiet section, in total silence. This is

only possible when using places so familiar to me, that it is second nature to

walk through them in my mind, and remember every minute detail.

When I was

brainstorming concepts for my musey room, I had trouble coming up with an idea

that would effectively encompass what I have learned from this course. I

realized that it would be impossible to give anyone a visual glimpse into my

newfound memory systems, due to their grotesquely abstract complexities that

make them so uniquely memorable. The reason that they cannot be explained to

another person is that they are so incredibly visual. This is largely a result of the practicality of rehearsing

poetry aloud. Due to people thinking you're crazy, and limited alone time, I

had to be able to utilize silence during the construction of my memory

theaters. This is a difficulty I ran into while learning Kubla

Kahn. To accommodate for the restraints presented, I created

imagery for the entire poem without speaking a single word. Before I ever

practiced the poem in length for the first time, I had detailed images

constructed in my mind. I did almost all of my memory training this semester on

the third floor of the library, in the quiet section, in total silence. This is

only possible when using places so familiar to me, that it is second nature to

walk through them in my mind, and remember every minute detail. For some time now I have thought about the

similarities between the Globe Theater and Camillo's memory palace. While

Camillo intended his building to be a tool used to enhance individual memory, I

see no reason why this could not be utilized by performers. Who knows, maybe

Renaissance actors practiced their lines in the the empty globe, using the

segregated sections of seating as loci for storing multiple memory

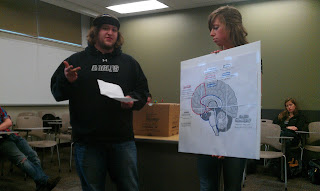

palaces. The model I presented to the class is a hybrid of these two

structures. It is a design in which the orator can utilize the spatial nature

of his memory to trigger multiple sections of dialogue from different,

emotionally charged core images he/she has placed around the theater. While I

doubt that my design will be published in any groundbreaking architecture

journals, I do think that the concept could be effectively utilized by any type

of performance oriented structure.

For some time now I have thought about the

similarities between the Globe Theater and Camillo's memory palace. While

Camillo intended his building to be a tool used to enhance individual memory, I

see no reason why this could not be utilized by performers. Who knows, maybe

Renaissance actors practiced their lines in the the empty globe, using the

segregated sections of seating as loci for storing multiple memory

palaces. The model I presented to the class is a hybrid of these two

structures. It is a design in which the orator can utilize the spatial nature

of his memory to trigger multiple sections of dialogue from different,

emotionally charged core images he/she has placed around the theater. While I

doubt that my design will be published in any groundbreaking architecture

journals, I do think that the concept could be effectively utilized by any type

of performance oriented structure. It has been

my experience that college is a give and take relationship. For every bit of

effort that you put in, you take out a much larger reward. Nowhere is this more

evident than in the study of literature. As Megan Mother of the Muses says in

her blog, people frequently question the validity of what we study, and are

completely out of the loop as to what benefits could possibly be reaped from an

English degree. Jennifer of the Falling Waters believes that the study of literature

is a process of discovery and personal growth. As a convert to the program, I

like to think of myself as evidence to this theory. In my previous studies, I

treated school as secondary to first tracks and tight lines. Midway through my

university career, I basically stumbled into literature. A broken collar bone

and newly found free time fostered a fervor to expand my knowledge that I had

never previously experienced. People often ask how horrible my two clavicle

surgeries were, and I startle them by replying that it was the best thing that

ever happened to me. While I still cherish my time in the mountains, two trips

to the ER in the span of 3 months served as a serious reality check. Your body

can only go so hard for so long, but the mind is limitless. It was not

the literature itself that served as the catalyst for the

growth I experienced, but it is the skills I gained, the people I have met, and

the discoveries I have made about myself along the way that make me so grateful

for my shoulder's violent clash with terra firma. If I ever lose motivation in

my studies, all I have to do is reach up and feel the screws lining the top of

the metal plate that sits just beneath the surface my skin, and I am reminded

to stay focused.

It has been

my experience that college is a give and take relationship. For every bit of

effort that you put in, you take out a much larger reward. Nowhere is this more

evident than in the study of literature. As Megan Mother of the Muses says in

her blog, people frequently question the validity of what we study, and are

completely out of the loop as to what benefits could possibly be reaped from an

English degree. Jennifer of the Falling Waters believes that the study of literature

is a process of discovery and personal growth. As a convert to the program, I

like to think of myself as evidence to this theory. In my previous studies, I

treated school as secondary to first tracks and tight lines. Midway through my

university career, I basically stumbled into literature. A broken collar bone

and newly found free time fostered a fervor to expand my knowledge that I had

never previously experienced. People often ask how horrible my two clavicle

surgeries were, and I startle them by replying that it was the best thing that

ever happened to me. While I still cherish my time in the mountains, two trips

to the ER in the span of 3 months served as a serious reality check. Your body

can only go so hard for so long, but the mind is limitless. It was not

the literature itself that served as the catalyst for the

growth I experienced, but it is the skills I gained, the people I have met, and

the discoveries I have made about myself along the way that make me so grateful

for my shoulder's violent clash with terra firma. If I ever lose motivation in

my studies, all I have to do is reach up and feel the screws lining the top of

the metal plate that sits just beneath the surface my skin, and I am reminded

to stay focused.

If I were to walk into the Hauf Brau 30 years

from now, and run into Copious Kyle, it would take a minute for us to recognize

each other. The aging effects of time would have weathered our faces, we would

no longer have the energy of youth about us, but eventually we would recognize one

another. We might not recall who Joshua Foer was, or what Giordano Bruno

theorized about; but I would imagine that we would remember our epithets,

perhaps a few funny stories from that class we had long ago back in our college

days. I know for certain however, that we would remember Michael Sexson.

If there were such a thing as a wizard of the

English department, Dr. Sexson would fill that role. I have never met someone

that can so effortlessly recall passages of poetry, literature, and song at the

drop of a hat. He has never directly said so, but I think he would agree with

my give and take theory. To me anyways, that is how his classes work. If you so

desire, you can simply coast through them and get by with minimal effort. On

the other hand, you can challenge yourself to become truly absorbed in the

material, and come out on the other side an improved scholar. We have excellent

examples of that within our class; from Jenny's novel, to Nick's sock-knocking

off blog entries, to Cameron's fascination with learning the details

of scripture, there are people leading the charge of self-powered learning

right amongst our midst.

If there were such a thing as a wizard of the

English department, Dr. Sexson would fill that role. I have never met someone

that can so effortlessly recall passages of poetry, literature, and song at the

drop of a hat. He has never directly said so, but I think he would agree with

my give and take theory. To me anyways, that is how his classes work. If you so

desire, you can simply coast through them and get by with minimal effort. On

the other hand, you can challenge yourself to become truly absorbed in the

material, and come out on the other side an improved scholar. We have excellent

examples of that within our class; from Jenny's novel, to Nick's sock-knocking

off blog entries, to Cameron's fascination with learning the details

of scripture, there are people leading the charge of self-powered learning

right amongst our midst.Thank you Dr. Sexson, for fostering the growth of your students in yet another unforgettable class.